The Trucking Industry Was Ripe for Disruption, and This Tech Company Made Billions Doing It

[ad_1]

Susan Rockey loved trucking. What she hated was compliance.

Lured by the call of the open road after years of working as an ER tech and running group homes for emotionally disturbed kids, she took a job in 2015 at Conner Logistics. Mostly she drove an 18-wheeler, a reefer — meaning “ree-frigerated,” as she’s had to explain way too often — hauling meat and produce across America. But half the time, she was rooting around in the truck for a pencil and her three-ringed binder to enter her hours on the required gridded paper. She needed a ruler, too, and often had to fax the logs in from the next truck stop. All drivers had to do some version of this; no one liked the rigamarole. “There was a lot of noncompliance, a lot of cheating,” she says.

One day, she found an app called KeepTruckin. The name wasn’t fancy. It was free. It solved her problem.

The app also solved a problem for the guy who made it, Shoaib Makani, who was for many reasons an unusual figure in trucking at the time. An immigrant from Pakistan, he’d become a tech-focused venture capitalist and was doing well at it in 2013. But while his peers were falling all over themselves for crypto and AI, Makani saw white space in tar, tires, and 80,000-pound semis. The industry was almost untouched by outsiders in Silicon Valley. He just needed a way in.

Related: How Apps Are Changing Our Everyday Lives

His KeepTruckin app opened the door, and it led to a company that’s grown by 75% year-over-year. In 2021, it was valued at north of $2 billion with annual recurring revenue of $150 million, and by the end of 2022, it expects to have 4,300 employees. But in a way, his app is almost too successful. At the beginning, Makani didn’t see quite how big the opportunity was; seizing it in full has meant rethinking a lot about his business — and running the risk of upsetting truckers like Susan Rockey in the process.

After all, sometimes the biggest opportunities are the ones you can’t spot until you’re further down the road. But once you’ve gone that far, is there any turning back?

Image Credit: Courtesy of KeepTruckin

Makani was born 38 years ago in Pakistan and moved with his family to Texas at the age of two. They eventually settled in Little River Academy, a rural town of about 1,000 where they were the rare immigrants. Makani still loves it, but found his way out: first to the London School of Economics and Political Science, then to Silicon Valley doing business development at Google’s AdMob. He’d moved on to Khosla Ventures in 2011, leading investments in startups like Instacart and Yammer, when he met Joe Kraus at Google Ventures. “Shoaib was very hungry,” says Kraus, now president of Lime. “He had a desire to put a dent in the universe. I told him: ‘If you ever start a company, I’d love to be working with you.’”

Makani was itching to build something. He was struck by how the vast majority of startups were improving life for those in the digital economy — “but the same was not happening for the businesses and the people who did physical work,” he says. There were whole areas of industry that hadn’t been irrigated by technology, and the more he thought about the disconnect, the faster he wanted to get in. He’d always been fascinated by trucks; 72% of goods in the U.S. are moved by them. Interested in learning more about the industry, he suggested to Obaid Khan — his brother-in-law who also wanted to start something — that he go see what he could find out.

Khan couldn’t glean much from analyst reports, so he started going up and down California’s I-5 and hanging out at truck stops. “I would be the awkward guy saying, ‘Hey, I’ll give you this $15 Starbucks gift card. Just tell me: How do you do laundry? Keep in touch with your family? Do banking?’” he says. “I made it broad.” Once the drivers got talking — like Rockey — they vented about compliance and the obnoxious gridded paper and rulers to enter their hours of service. But they were also concerned about a new law that seemed to be coming down the pipeline.

Related: Technology Is Already Disrupting Our Lives. What Will the Future Look Like?

A 2012 congressional act, Khan and Makani learned, had just directed the Department of Transportation to develop regulations to mandate electronic logging devices (ELDs). This was a major change, and a challenge. An ELD is a little box installed in the truck and connected to the engine that tracks things like driving hours and miles covered. It would completely replace the compliance work on the gridded paper, but drivers bristled at the idea of Big Brother moving into their motors.

Makani already had a million ideas for a company that provides technological solutions to truckers, but he suddenly saw compliance, with its shifting regulations and obvious pain points, as the perfect entry. It wasn’t clear when, or even if, the authorities would succeed at passing a mandate. “This ELD regulation had been deliberated for almost a decade and there were lots of legal challenges,” he says, “so we weren’t betting on that.” But for the moment, truckers were frustrated with compliance, so he would create his own tech solution.

Makani launched the company with Khan, along with a third founder, Ryan Johns. Then he sunk his intention like a crampon into the climb, building an app to enter compliance data and spending nearly a week at a Denny’s in Seattle asking truckers for their feedback. As for the name? “Shoaib would always close our meetings with ‘Keep truckin’!” says Khan. It stuck, and clients loved it.

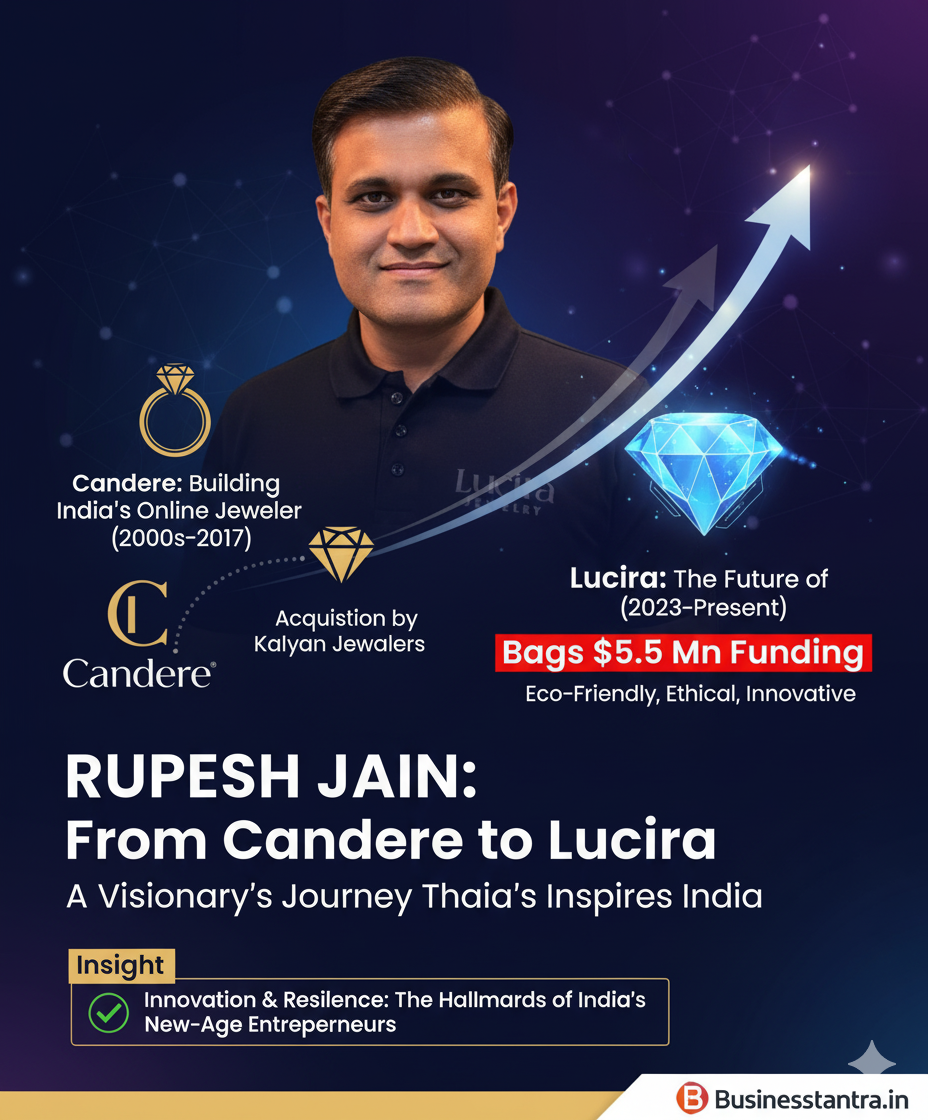

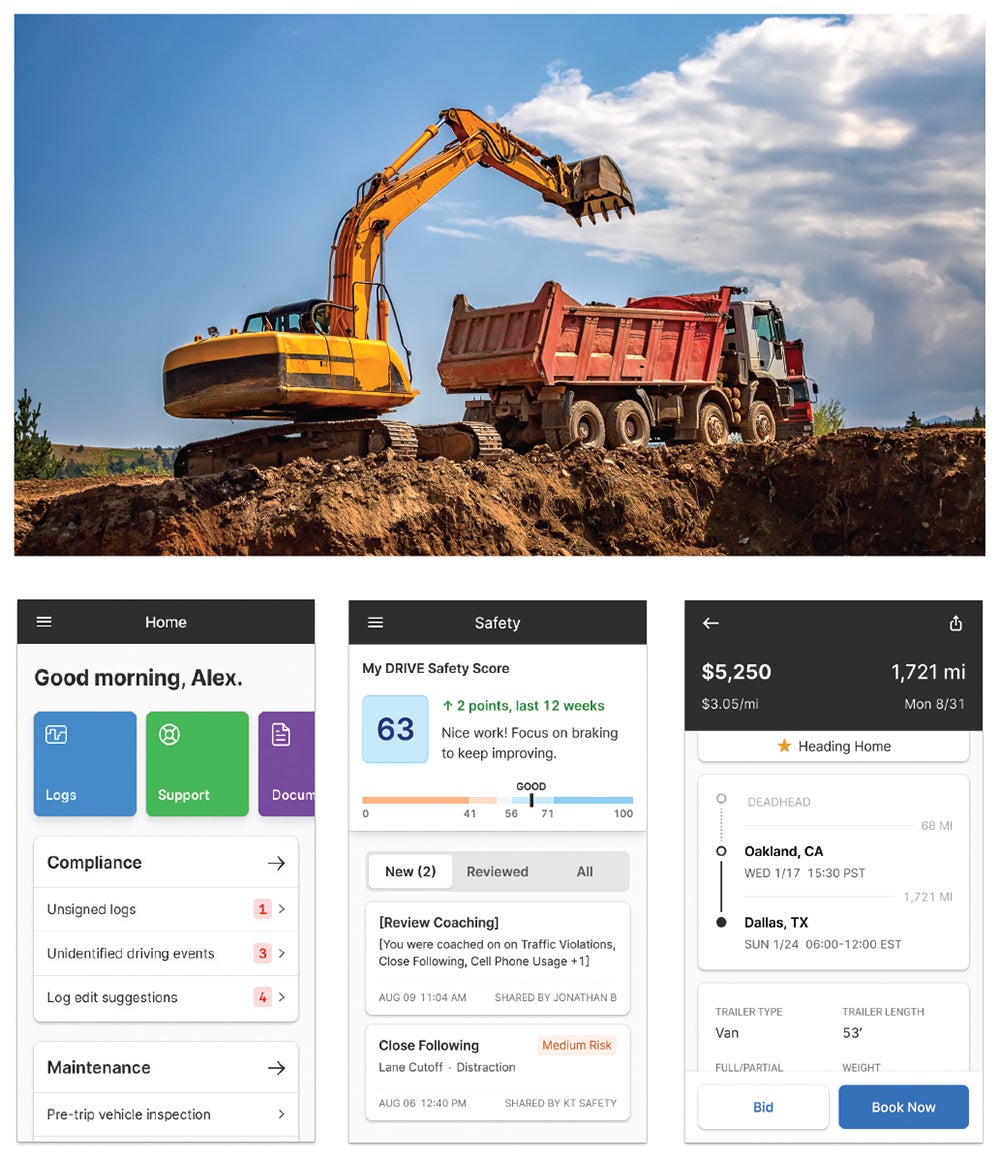

KeepTruckin is expanding to other industries. Now many construction clients use products like this one, which alerts managers to risky driving.

Image Credit: Courtesy of KeepTruckin

Once they had the app, Makani and Khan decided to make it free. They wanted to create value for their customers and build trust before making them pay — you couldn’t get anywhere without trust. The plan was to grow the base with as many truckers as possible; then they’d upsell other products to those in the industry.

For four years, no revenue came in, but more than a million drivers downloaded the app and gave it high ratings. Meanwhile, Makani started developing an ELD, the device regulators were trying to hash out a mandate for, in hopes that it would become KeepTruckin’s first monetizable product. As it turned out, the regulators succeeded. Beginning in December 2017, commercial trucks were required to have ELDs.

Suddenly, there were a lot of people like Lauren Abrams, who needed to outfit her fleet of 300 with the new devices. She’s a product manager at Reliable Carriers, which transports luxury car shipments worth up to $63 million each load, and she discovered that several of her employees were using KeepTruckin’s app. “By then, KeepTruckin already had a pretty good reputation among drivers,” she says. “And that went a long way, compared to some of these other ELD companies that were more looked at as watchdogs. Their strategy of how they came into the industry was really smart.”

While the KeepTruckin app was no longer as useful on its own, it worked well with the company’s ELD product and was expanded to include features like telling drivers where to pick up the next load and guiding them through inspections. Meanwhile, sales of the ELDs took off, and Makani began to think about all those other ideas he’d had. As he saw it, the company faced a fork in the road: It could either become an online marketplace for individual truckers to find work, or it could become a platform for fleet managers to automate many of their tasks. Ultimately, he chose the fleet managers, where the money and big purchasing decisions are.

Related: Innovation is an Incremental Process. Here are 3 Ways to Reach Your Big Idea.

Makani started raising more capital (as of today, $450 million), invested in automation expertise, and acquired two AI companies. He also hired Jai Ranganathan, who’d been at Uber specializing in machine learning and data-driven technology apps, to head up the product team. Under Ranganathan’s direction, KeepTruckin’s platform expanded into things like GPS, maintenance, spend management, and safety — mostly enabled by tracking devices in trucks. Now, fleet managers and operators not only know where their vehicles are at any given time, but they can do things like predict when cargo will arrive, monitor fuel use, and determine driving behavior that is causing drops in mileage (corrective actions can give up to 10% savings, says Ranganathan). They can also record accidents and spot employees out on the road who are driving poorly in real time.

Just as KeepTruckin’s founders had learned so much by hanging out at truck stops and diners, their teams gave their new customers products to play with and always invited suggestions. Abrams says she worked extensively with KeepTruckin on adjusting the ELD to more efficiently handle pairs of drivers, like husband and wife teams who often trade off to meet tight deadlines. Now, they’re going back and forth on a side camera feature.

Cameras, as it happened, were another turning point for the company.

In April, KeepTruckin’s dashcams will look a little different. It’s the next turn in an adventurous journey.

Image Credit: Courtesy of KeepTruckin

In theory, truckers should welcome dashboard cameras. Some 80% of crashes involving commercial vehicle operators aren’t caused by them, says Ranganathan — but they’re often blamed for the accidents anyway. “If you imagine an 18-wheeler in an accident with a Prius, it doesn’t matter who’s at fault; one side is not going to look like anything happened to them and the other side is going to be gone,” he says. Cameras could prove a trucker’s innocence. But drivers and owners were ambivalent. After all, the camera would be damning if an accident was their fault. They also saw it as a slippery slope — first the cameras would point outside, but what’s next? “If the truck I’m in ever gets a camera installed in it facing me, facing inside this truck, this home where I live in, I will stop the truck and quit on the spot,” YouTuber ‘Trucker Josh’ told his more than 100,000 subscribers in 2017.

Still, Makani saw a major opportunity in dashcams, just as he had with compliance. His clients were increasingly concerned with what were called “nuclear verdicts” — lawsuits over accidents with outsized penalties that top $10 million (one case had hit $280 million). So KeepTruckin introduced a simple road-facing camera in 2018. Once owners and managers saw the benefits, Makani figured, the company could roll out more sophisticated versions.

Conner Logistics signed on. By then, Susan Rockey had moved up from driver to operations safety manager and was known around the office as Mamma Sue. She’d been the one to suggest KeepTruckin. “We were ardent opposed-to-camera people,” she says. “But it didn’t take long to get over that.”

Soon after installing KeepTruckin’s cameras, they had a multi-vehicle collision where their driver was accused of hitting a passenger vehicle. The camera captured the real story: A car swerved into their truck’s lane and clipped it before spinning out. Quickly, accusations were dropped. CEO Sean Conner, a former police officer, remembers replaying the footage in slow motion, and noticing a child’s face through the car’s window looking up at the camera. “It was cool to see that the kid wasn’t injured,” he says. “The cameras have saved us 10 or 15 times since then.”

Related: Diversity and Technology Have the Power to Boost Business Revenues

By August of 2021, the market was a lot more accepting, and KeepTruckin launched its AI dashcam, which also had an inward-facing option. The product alerts managers if an employee isn’t driving safely — texting, drowsy, speeding, not wearing a seatbelt, braking aggressively, drifting out of lanes — so they can intervene immediately and provide coaching (which KeepTruckin also offers). That same month, a jury in Florida awarded a $1 billion penalty against the trucking companies involved in a road fatality — reinforcing the need for a product like this. “As a company,” says Reliable’s Abrams, who also bought the dashcams, “you have one bad accident and you’re done, closed for good.”

So far, KeepTruckin’s data shows their AI dashcams reduce accidents by 22% and safety incidents by 56%. That got the attention of insurance companies, several of which they now partner with, who give discounts for members that install the cameras — a major boost for sales.

“If you could have seen KeepTruckin four to five years ago, it was nothing,” says Rockey. “Now, at my desk, I’ve got it on three different screens: my fleet maps up on one; then I’m watching the safety videos created by alerts for phone use, no seatbelt, hard braking, et cetera; and sending coaching messages on the third. What keeps us coming back is that they continue to expand.”

Today, ironically, the expansion Makani is eyeing has nothing to do with trucking. More than 30% of his clients aren’t in the industry.

Instead, they’re in construction, drilling, agriculture, oil and gas, and field services — industries that also involve large equipment and trucks that need help with compliance, safety, and tracking data. More and more frequently, KeepTruckin has been building features for these clients, like Cascade, a leading environmental, water, and geotech drilling company, which wants to measure fuel burned by their rigs on the job site. “We get a tax credit for that,” says Alex Amort, vice president of compliance, “so it can be a huge gain, because we can burn up to 200 gallons a day.”

Over the last couple of years, Makani began to realize that trucking may not be the biggest opportunity for this company — and the name KeepTruckin is a potential barrier to entry for new industries and larger clients.

Again, he found himself at a fork in the road. His brand had projected a casual, insider vibe, which won the trust of the trucking industry. Should he risk it all with a rebrand? If he didn’t, would it limit the company’s potential? “It was a hard decision because you get attached to your name, and it becomes part of your identity,” Makani says. “By changing it, you lose a lot of brand equity.”

After much thought, he came to a conclusion: “Don’t let a name constrain your opportunity.” On April 12, 2022, the company will no longer be called KeepTruckin.

Related: 4 Ways Market Leaders Use Innovation to Foster Business Growth

The team considered many new names, but the winner was Motive. “It evokes movement and automotive, and also motivation, so there’s some connection to where we came from,” says Makani. “But importantly, it also is totally unbounded, because it is hard to know what the next problems we will solve are.”

He has some ideas. Motive is closely watching autonomous driving, and many of its products are ready to be adapted to driverless vehicles. It’s also building out financial services, including corporate cards that will be issued through Motive — a name roomy enough to go after those enterprise clients. And Makani wants to be clear: Motive hasn’t forgotten truckers. Among other things, the company is looking into a feature that finds drivers parking spots.

The rebrand will take time. Changing the assets — sales tools, customer invoices, stickers drivers put on their trucks, everything internal — is daunting. So is starting from scratch with name recognition. “But we’re growing this company for the next 50 years,” says Makani. “So a few years of effort to build this new brand? It will be very worthwhile.”

[ad_2]

Source link