ExplainSpeaking | How inflation beat the RBI: A recent history

[ad_1]

ExplainSpeaking-Economy is a weekly newsletter by Udit Misra, delivered in your inbox every Monday morning. Click here to subscribe

Dear Readers,

This week, on June 8, India’s central bank, the Reserve Bank of India, will announce its latest monetary policy statement. It is widely expected that the RBI will further raise the cost of money (that is, raise the interest rate) as well as cut down the amount of money in the financial system (that is, curb the liquidity) in a bid to control retail inflation.

To be sure, the consumer price index-based inflation — or CPI/retail inflation rate — that was until recently only hurting people is now becoming a political problem for the government.

But more than just the quantum of hike in the repo rate (the interest rate that RBI charges commercial banks when it lends money) what would be both of great interest and value is the RBI’s outlook on inflation.

For instance, how long does the RBI see inflation staying out of its comfort zone (that is, above 6%)? Or, when does the RBI expect inflation to be back to its target rate of 4%? How many more interest rate hikes does RBI expect to make? How significant has been the effect, in RBI’s view, of the government cutting taxes on domestic fuel prices? What is RBI’s outlook on India’s GDP growth especially during a phase of monetary tightening?

Last month, while addressing the 7th Annual Meeting of the Board of Governors of the New Development Bank, Union Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman reportedly claimed that India will grow by 9% (8.9% to be precise) in the current financial year. Is that possible? Especially when most of the economists not associated with the government peg the growth at 7% and that too rather grudgingly.

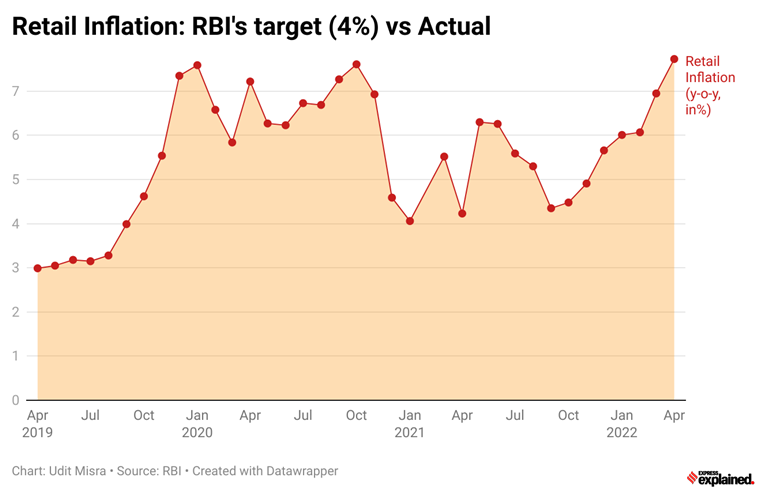

Today’s ExplainSpeaking will attempt to look back at how the RBI commented on inflation over the past two years. As Chart 1 below shows, retail inflation in India has been above the RBI’s target rate of 4% since October 2019. Only on three occasions (months) has retail inflation come close to 4% in the past 30 months.

Chart 1: Actual retail inflation vs the RBI target of 4%, over the last two years

Chart 1: Actual retail inflation vs the RBI target of 4%, over the last two years

Reading past monetary policy statements will serve at least two crucial purposes.

One, it will tell us when and where RBI dropped the ball on inflation. Two, it will set the context for everyone to better appreciate what RBI says on June 8th.

We pick up the story from the Monetary Policy Statement (MPS) of August 2019. As can be seen from chart 1, retail inflation was still comfortably below RBI’s target rate. However, within a few months, the story was about to go awry.

To be sure, the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) of the RBI sits once every two months — typically in February, April, June, August, October and December — to review its policy stance. Once in a while, in times of emergency, as it happened in early 2020 when Covid broke, the RBI meets off-cycle and announces a tweak to its policy stance.

When evaluating the RBI policy statements, it is also important to remember that when the MPC meets in a particular month, say August, retail inflation data is publicly available only up to June. In other words, typically, there is a two-month lag.

So, here’s what the MPC stated on inflation in August 2019:

“Retail inflation, measured by y-o-y change in the CPI, edged up to 3.2 per cent in June from 3.0 per cent in April-May, driven by food inflation, even as fuel inflation and CPI inflation excluding food and fuel moderated…The actual headline inflation outcome for Q1:2019-20 at 3.1 per cent was in alignment with these projections… The path of CPI inflation is projected at 3.1 per cent for Q2:2019- 20 and 3.5-3.7 per cent for H2:2019-20, with risks evenly balanced…The MPC notes that inflation is currently projected to remain within the target over a 12-month ahead horizon.”

Q1, Q2 etc. refers to quarters of the financial year. For instance, Q1 is made up of April, May and June; there are four quarters in a financial year. Similarly, H1 and H2 refer to the first and second half of the financial year. As such, for example, H2 refers to the six months from October to March.

In light of this benign inflation forecast, the MPC decided to cut the repo rate by 35 basis points (or by 0.35%) from 5.75% to 5.40%. A lower repo rate implies the cost of borrowing comes down for banks and that, in turn, allows banks to cut interest rates for the rest of the economy. So loans for everything from housing to education to starting a new business become more affordable, thus boosting economic activity and credit-fuelled demand in the economy.

MPC in October 2019:

“Retail inflation…moved in a narrow range of 3.1- 3.2 per cent between June and August. While food inflation picked up, fuel prices moved into deflation. Inflation excluding food and fuel softened in August…the CPI inflation projection is revised slightly upwards to 3.4 per cent for Q2:2019- 20, while projections are retained at 3.5-3.7 per cent for H2:2019-20 and 3.6 per cent for Q1:2020-21.”

Eventually, given the steadily weakening GDP growth momentum, the MPC decided to cut the repo rate by another 25 basis points from 5.4% to 5.15%.

Readers should recount 2019-20 also started with FM Sitharaman stating that the economy will grow by 8%. Eventually, the economy grew by 2.8% that financial year.

But keep an eye on the inflation chart (1) as well as you read the next few statements because the retail inflation rate almost doubled between September 2019 when it was 3.99% — almost exactly what RBI wanted — to 7.6% in January 2020. Also, note that this was the pre-Covid period.

MPC in December 2019:

“Retail inflation… increased sharply to 4.6 per cent in October, propelled by a surge in food prices…Turning to the drivers of CPI, food inflation spiked to 6.9 per cent in October – a 39-month high – pushed up by a sharp increase in prices of vegetables due to heavy unseasonal rains…the CPI inflation projection is revised upwards to 5.1- 4.7 per cent for H2:2019-20 and 4.0-3.8 per cent for H1:2020-21”.

The sudden spike in inflation made the RBI pause its repo rate cuts despite continued weakness in economic growth.

MPC in February 2020:

“Retail inflation… surged from 4.6 per cent in October to 5.5 per cent in November and further to 7.4 per cent in December 2019, the highest reading since July 2014…the CPI inflation projection is revised upwards to 6.5 per cent for Q4:2019-20; 5.4-5.0 per cent for H1:2020-21; and 3.2 per cent for Q3:2020-21.”

The MPC felt that this spike was primarily due to the spike in onion prices. But, notwithstanding its rosy projection of 3.2% inflation in Q3 (October to December) of FY21, it also believed that the inflation outlook was becoming increasingly uncertain; remember that Coronavirus had started disrupting the western economies.

The RBI was increasingly in a bind: Raise interest rates to control inflation or cut them to boost decelerating growth momentum.

Newsletter | Click to get the day’s best explainers in your inbox

“The MPC recognises that there is policy space available for future action. The path of inflation is, however, elevated and on a rising trajectory through Q4:2019-20. The outlook for inflation is highly uncertain at this juncture. On the other hand, economic activity remains subdued and the few indicators that have moved up recently are yet to gain traction in a more broad-based manner. Given the evolving growth-inflation dynamics, the MPC felt it appropriate to maintain the status quo. Accordingly, the MPC decided to keep the policy repo rate unchanged and persevere with the accommodative stance as long as necessary to revive growth, while ensuring that inflation remains within the target.”

MPC in March 2020:

“In February, CPI headline inflation was projected at 6.5 per cent for Q4:2019-20. The prints for January and February 2020 indicate that actual outcomes for the quarter are running 30 bps above projections, reflecting the onion price shock.”

However, MPC was of the view that “macroeconomic risks, both on the demand and supply sides, brought on by the pandemic could be severe. The need of the hour is to do whatever is necessary to shield the domestic economy from the pandemic.”

It was expected that demand compression due to Covid disruptions would weaken the spike in inflation. As such, MPC cut the repo rate by another 75 basis points from 5.15% to 4.40%.

MPC in May 2020:

“Retail inflation… moderated for the second consecutive month in March 2020 to 5.8 per cent after peaking in January. This was mainly due to food inflation easing from double digits in December 2019 – to January 2020. In April, however, supply disruptions took a toll and reversed the softening of food inflation, which surged to 8.6 per cent from 7.8 per cent in March.”

As such even though the RBI stated that the inflation outlook is quite uncertain, it did expect that depressed demand, normal monsoon (read decent food production) combined with the base effect will “pull down headline inflation below target in Q3 and Q4 of 2020- 21.”

As chart 1 shows, in reality, despite India going into a technical recession, retail inflation hovered between 6.2% and 7.6% between April and November of 2020.

But the apprehensions of a complete collapse in demand made the RBI cut repo rates by another 40 basis points to 4%.

MPC in August 2020:

By August it was clear to the RBI that high inflation will stay until some statistical relief happens via the high base effect. “…headline inflation may remain elevated in Q2:2020-21, but may moderate in H2:2020-21 aided by large favourable base effects.

MPC opted for the status quo on the repo rate.

“Given the uncertainty surrounding the inflation outlook and taking into consideration the extremely weak state of the economy in the midst of an unprecedented shock from the ongoing pandemic, it is prudent to pause and remain watchful of incoming data as to how the outlook unravels.”

MPC in October 2020:

“Headline CPI inflation increased to 6.7 per cent during July-August 2020 as pressures accentuated across food, fuel and core constituents on account of supply disruptions, higher margins and taxes.”

Further, it stated: “CPI inflation is projected at 6.8 per cent for Q2:2020-21, at 5.4-4.5 per cent for H2:2020-21 and 4.3 per cent for Q1:2021-22”.

Note the change in RBI’s expectations for the second half of the financial year: from below the target (4%) to as high as 5.4% in H2.

Also note that by October 2020, India was completing one full year of retail inflation being uncomfortably high. And the weight of this failure showed up in the policy statement but the RBI chose to view high inflation as transitory and see through it.

“The MPC is of the view that revival of the economy from an unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic assumes the highest priority in the conduct of monetary policy. While inflation has been above the tolerance band for several months, the MPC judges that the underlying factors are essentially supply shocks which should dissipate over the ensuing months as the economy unlocks, supply chains are restored, and activity normalises. Accordingly, they can be looked through at this juncture while setting the stance of monetary policy.”

The RBI, which is legally mandated to contain inflation as its primary objective, was preferring to boost growth instead.

Net result: The MPC decided “to maintain status quo on the policy rate in this meeting and await the easing of inflationary pressures to use the space available for supporting growth further”.

MPC in December 2020:

The RBI continued to be surprised by the increase in inflation.

“CPI inflation rose sharply to 7.3 per cent in September and further to 7.6 per cent in October 2020, with some evidence that price pressures are spreading. Food inflation surged to double digits in October across protein-rich items including pulses, edible oils, vegetables and spices on multiple supply shocks. Core inflation, i.e., CPI excluding food and fuel, also picked up from 5.4 per cent in September to 5.8 per cent in October“.

As such, the RBI stated that “the outlook for inflation has turned adverse relative to expectations in the last two months”.

“CPI inflation is projected at 6.8 per cent for Q3:2020-21, 5.8 per cent for Q4:2020-21; and 5.2 per cent to 4.6 per cent in H1:2021-22,” stated the MPC further.

Note the repeated revisions in the inflation forecast for the same period — showing how RBI consistently not only overlooked inflation concerns but also underestimated the inflationary pressures.

But the RBI was also quite clear about where its priorities lay. “The MPC is of the view that inflation is likely to remain elevated, barring transient relief in the winter months from prices of perishables. This constrains monetary policy at the current juncture from using the space available to act in support of growth.“

MPC in February 2021

At long last, inflation had simmered down a bit.

“After breaching the upper tolerance threshold of 6 per cent for six consecutive months (June-November 2020), CPI inflation fell to 4.6 per cent in December on the back of easing food prices and favourable base effects.”

This led to a recalibration of outlook.

“CPI inflation has been revised to 5.2 per cent in Q4:2020-21, 5.2 per cent to 5.0 per cent in H1:2021-22 and 4.3 per cent in Q3: 2021-22.”

Even so, the projected inflation was still higher than the RBI’s target of 4%. As such, the repo rate remained unchanged.

However, as chart 1 shows, between the December of 2020 and 2021, retail inflation crossed the 6% mark just twice. As such even though inflation was not at 4%, it was also not completely out of control.

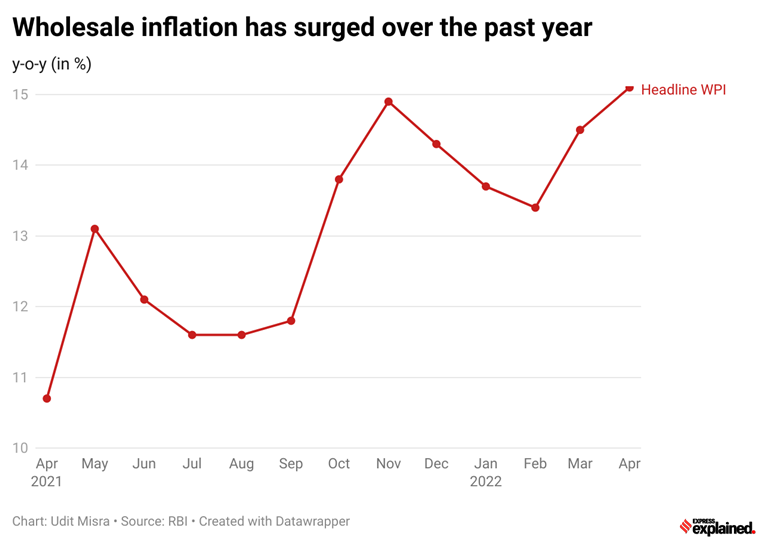

It is another matter though that wholesale inflation took over the baton from April 2021 onwards and has since clocked in double digits for 13-straight months (see chart 2). This was significant even though wholesale inflation is not the variable RBI targets.

Chart 2: A look at the wholesale inflation in the past year

Chart 2: A look at the wholesale inflation in the past year

MPC in April 2021:

“Headline inflation increased to 5.0 per cent in February after having eased to 4.1 per cent in January 2021… core inflation registered a generalised hardening and increased by 50 basis points to touch 6 per cent.”

While headline inflation was relatively contained, RBI was increasingly concerned about core inflation — which takes more time to rise and more time to decline — as it started to test the comfort zone itself.

Imported inflation was another concern.

“On imported inflation from global commodity prices, urgent concerted and coordinated policy actions by Centre and States can mitigate domestic input costs such as taxes on petrol and diesel and high retail margins.”

The spike in Covid cases during, what later came to be known as the second Covid wave, this period suggested a softening of demand and, as such, inflation.

End result: No change in repo rate.

MPC in June 2021:

“Headline inflation registered a moderation to 4.3 per cent in April from 5.5 per cent in March, largely on favourable base effects,” states the policy statement.

“CPI inflation is projected at 5.1 per cent during 2021-22: 5.2 per cent in Q1; 5.4 per cent in Q2; 4.7 per cent in Q3; and 5.3 per cent in Q4:2021-22,” stated the MPC.

MPC in August 2021:

“Headline CPI inflation plateaued at 6.3 per cent in June after having risen by 207 basis points in May 2021,” stated the MPC.

Unsurprisingly, their inflation projections were moved up a notch yet again. “… CPI inflation is now projected at 5.7 per cent during 2021-22: 5.9 per cent in Q2; 5.3 per cent in Q3; and 5.8 per cent in Q4 of 2021-22.”

What is interesting to note in this statement is the reiteration by the MPC that inflation pressures are “transient”.

“The current assessment is that the inflationary pressures during Q1:2021-22 are largely driven by adverse supply shocks which are expected to be transitory.”

RBI yet again underscored its preference for boosting growth instead of containing inflation: “The nascent and hesitant recovery needs to be nurtured through fiscal, monetary and sectoral policy levers. Accordingly, the MPC decided to keep the policy repo rate unchanged at 4 per cent and continue with an accommodative stance as long as necessary to revive and sustain growth on a durable basis and continue to mitigate the impact of COVID-19 on the economy, while ensuring that inflation remains within the target going forward.“

MPC in October 2021:

“Headline CPI inflation at 5.3 per cent in August softened for the second consecutive month … Core inflation, i.e. inflation excluding food and fuel, remained elevated and sticky at 5.8 per cent in July-August 2021…With core inflation persisting at an elevated level, measures to further ameliorate supply-side and cost pressures, including through calibrated cuts in indirect taxes on petrol and diesel by both Centre and States, would contribute to a more durable reduction in inflation and anchoring of inflation expectations,” stated the MPC.

By now, core inflation had started remaining persistently high and at least one member of the MPC — Prof. Jayanth R. Varma — “expressed reservations” about the RBI’s continued “accommodative” stance.

When one looks at the data — retail inflation started its latest climb in September last year — it is hard to fault with Varma’s reservations.

MPC in December 2021:

“Core inflation or CPI inflation excluding food and fuel remained elevated at 5.9 per cent during September-October,” it stated but again reiterated its preference to support growth.

“Considering it appropriate to wait for growth signals to become solidly entrenched while remaining watchful on inflation dynamics, the MPC decided to keep the policy repo rate unchanged at 4 per cent and to continue with an accommodative stance as long as necessary to revive and sustain growth on a durable basis.”

This is crucial again since December is the month when retail inflation yet again breached the 5% mark.

MPC in February 2022:

By now it became clear that headline CPI inflation had edged up to 5.6 per cent in December even as core inflation was now hovering around 6%.

Yet, RBI was content with its projections: “Since the December 2021 MPC meeting, CPI inflation has moved along the expected trajectory. “

In fact, it went further: “The MPC notes that inflation is likely to moderate in H1:2022-23 and move closer to the target rate thereafter, providing room to remain accommodative.”

In particular, MPC projected CPI inflation for 2022-23 at 4.5 per cent.

Prof Varma again expressed reservation with the MPC’s accommodative stance.

Later on in February, after speculations over several weeks if not months, Russia invaded Ukraine and gave yet another massive supply shock to the global economy.

MPC in April 2022:

By now the RBI found that even without any direct impact of the Ukraine conflict, headline CPI inflation had edged up to 6.0 per cent in January 2022 and 6.1 per cent in February. Core inflation, too, hovered around 6%. Unsurprisingly, the inflation projection for 2022-23 was scaled from 4.5% in February to 5.7 per cent.

What was remarkable about this policy statement was the fact that despite the inflation projection being ramped up by 1.2 percentage points, the RBI still dithered from raising interest rates.

This, in turn, set the stage for a mid-cycle rate hike that was witnessed in May.

MPC in May 2022:

“In March 2022, headline CPI inflation surged to 7.0 per cent from 6.1 per cent in February, largely reflecting the impact of geopolitical spillovers. Food inflation increased by 154 basis points to 7.5 per cent and core inflation rose by 54 bps to 6.4 per cent,” noted the MPC.

By now Inflation was a global phenomenon.

“The IMF projects inflation to increase by 2.6 percentage points to 5.7 per cent in advanced economies in 2022 and by 2.8 percentage points to 8.7 per cent in emerging market and developing economies.

Finally, the RBI raised the repo rate by 40 basis points. The repo now stands at 4.40%.

UPSHOT:

RBI’s primary goal is to maintain price stability in the economy. To this end, it is legally required to ensure retail inflation is at 4% (with a leeway of two percentage points on either side).

Retail inflation has been persistently high in India since late 2019.

As can be seen from the RBI’s monetary policy statements, more often than not, the central bank chose to see through inflation, largely expecting it to moderate on its own, while focussing its energies on boosting growth.

As things stand, it is hard to say which of the two key variables — retail inflation or real GDP growth — will grow at a higher rate in the current financial year.

Which variable will be higher in FY23? Share your views and queries at udit.misra@expressindia.com

Stay safe

Udit

[ad_2]

Source link