Explained: Making sense of exchange rate

[ad_1]

On Monday, during intra-day trade, the Indian rupee hit an all-time low exchange rate of 77.6 against the US dollar. At the time of going to print, it was 77.20 to a dollar. The previous lowest was 76.9. It has been a sharp fall in a matter of days: The rupee was at 76 to a dollar on May 5, when the US Federal Reserve raised interest rates.

What does exchange rate signify?

The rupee’s exchange rate vis-a-vis a particular currency, say the US dollar, tells us how many rupees are required to buy a US dollar. To buy (import) a US product or service, Indians need to first buy the dollars and then use those dollars to buy the product. The same holds true for Americans buying something from India.

If the rupee’s exchange rate “falls”, it implies that buying American goods would become costlier. At the same time, Indian exporters may benefit because their goods now are more attractive (read cheaper) to the American customers.

How is it determined?

In a free-market economy, the exchange rate is decided by the supply and demand for rupees and dollars.

Imagine that in the beginning, one rupee was equal to one dollar. After a year, Indians demand more dollars in comparison to Americans demanding the rupee. In such a case, the exchange rate will “fall” or “weaken” for rupee and “rise” or “strengthen” for dollar.

However, in India, the exchange rate is not fully determined by the market. From time to time, the RBI intervenes in the foreign exchange (forex) market to ensure that the rupee “price” does not fluctuate too much or that it doesn’t rise or fall too much all at once.

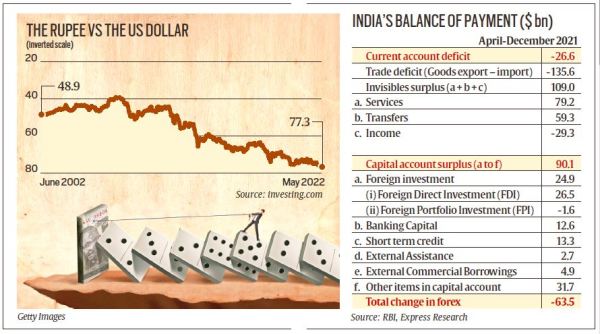

The Rupee vs the US Dollar

The Rupee vs the US Dollar

What determines the rupee’s demand and supply vis-a-vis other currencies?

This is best understood by looking at India’s balance of payment (BoP). The BoP is essentially the overall ledger of how much rupee was demanded by the rest of the world and how much foreign currency (that is, currencies of all countries) was demanded by Indians.

The table shows the BoP for the period April-December in the last financial year.

The BoP is divided into two “accounts” — current and capital. Think of them as two buckets for two different types of transactions between Indians and foreign nationals. Current account refers to all transactions that are related to current consumption; capital account refers to transactions for investment purposes.

Each bucket is sub-divided into smaller buckets. This allows policymakers and analysts to better understand the dynamics of the relative demand for rupees (by foreigners) and forex (among Indians).

In any year, Indians (and/or Indian entities such as companies and governments) and foreign nationals (and/or entities) transact in several different ways. All such transactions generate demand for rupees (among foreigners) and forex (among Indians).

All transactions involving export or import of goods (cars, gadgets etc) are logged under the “trade account” within the current account.

But people also trade in “invisibles”. Essentially, this refers to export and import of services (such as an Indian company selling software to an American firm, or a European bank providing financial services to some Indians, or simply Indians working abroad sending back money to their families in India).

The capital account, on the other hand involves investments (such as an Indian buying land in the US, or a Japanese firm investing in the Indian stock exchange) as well as exchange of loans between India and other countries.

How does the rupee’s exchange rate fluctuate?

The trigger can come from several directions. For simplicity, consider two scenarios that are unfolding these days.

One, crude oil prices go up sharply. For India, which imports 80% of its oil, the fallout would be that it would need more dollars to buy crude oil in the international market. That, in turn, would weaken the rupee because India’s demand for dollars would have gone up while the world’s demand for the rupee stayed the same. This would show up as a trade deficit as well as the current account deficit in the BoP table. When more rupees/dollars go out of a BoP category than what comes in, it is shown with a “minus” mark.

Two, the US central bank raises its interest rates and looks set to raise them further in the future. Global investors who had been putting their money in India (for which they demanded rupees) would consider taking it out and investing in the US (for which they would demand dollars instead). Again, the rupee would weaken. Such a transaction would be recorded in the Capital Account.

What is the RBI’s role in this?

The most important thing about the BoP is that the balance of payment always balances. In other words, a deficit in the current account must be balanced by a surplus in the capital account, or vice versa.

If there was no RBI to intervene, then as money started flowing out of India on account of oil and US interest rates, the rupee’s exchange rate would have fallen and continued to do so until buying from India and investing here became attractive again. This process might imply massive fluctuations.

This is where RBI comes in. To soften the rupee’s fall, the RBI would sell in the market some of the dollars it has in its forex reserves. This will soak up a lot of rupees from the market, thus moderating the demand-supply gap between rupee and dollars. This is why the RBI’s forex reserves have gone down sharply since the war in Ukraine started in February.

Between April and December, the situation was the opposite. There was a $90 billion surplus on the capital account — meaning net-net $90 billion came into the country on such transactions — and a $26.6 billion deficit in the current account — meaning net-net $26.6 went out of the country on such trades.

Left unaddressed, the excess $63.5 billion would have led to a rise in the rupee’s exchange rate. To moderate, the RBI bought this excess amount of dollars (by paying rupees in the market) and added it to its forex reserves.

Newsletter | Click to get the day’s best explainers in your inbox

Is a fall in the exchange rate necessarily a bad thing?

Indeed, the exchange rate is often taken as a marker of the relative strength of an economy. Most developing economies tend to run deficits on their trade and current accounts.

The eventual impact of a fall depends on several factors. For instance, a fall can help India’s exporters — unless they importing raw materials, which would become costlier.

[ad_2]

Source link