Explained: Five indicators that RBI dropped the ball on managing inflation

[ad_1]

The RBI has argued that it is concerned about the rising level of inflation. By raising the repo rate, the RBI hopes to incentivise people to spend less and save more, thus cooling down demand in the economy and, by extension, prices.

The move — to have such a meeting and to raise the interest rates — is, at two different levels, both surprising and obvious. It is surprising because the RBI’s MPC meets once every two months — and the meeting this week was not scheduled. The MPC had met in February and April, and was set to meet next in June.

However, the RBI’s actions are also unsurprising — because, for a while now, evidence has been accumulating that the RBI, whose primary responsibility is to maintain price stability in the economy and control inflation, has been failing to do its job.

In fact, the sudden, unexpected decision to raise rates is just the latest example of how RBI has been underestimating inflation and repeatedly choosing to see through rising prices. Here are five indicators that show how the RBI had fallen behind the curve.

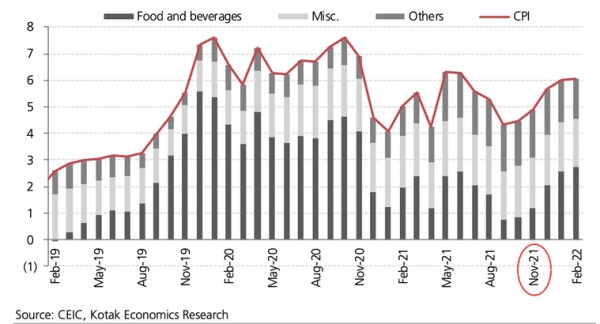

1. Inflation has been rising for over two years.

By law, the RBI is supposed to target retail inflation at 4%. The law, however, prescribes some leeway to the RBI; it allows for retail inflation to vary by 2 percentage points on either side. So, in a particular month, the RBI could allow inflation to be 2% or 6%.

However, the central point is that on the whole, inflation should be around 4%. The leeway of 2% to 6% does not mean that the RBI can allow inflation to stay at 6% all through. This is central to understanding how the RBI has been failing in its mandate.

Look at Chart 1 (below) for retail inflation.

Since October 2019, there’s been just one month when retail inflation has been close to 4%. In all other months, even those of the nationwide Covid-19 lockdown in 2020, saw inflation staying well above 4%, and often even above the 6% mark.

2. The inflation has not been “transitory”.

The reasons for high inflation have tended to change over the months but overall, as Chart 1 shows, inflation has remained high. Sometimes it has been fuelled by high crude oil prices as well as the high level of taxation on such fuels — as indeed is happening now — and sometimes it has been kicked up by the scarcity of food articles, perhaps because of unseasonal rains.

And yet, for the most part since October 2019, the RBI has very openly given first preference to boosting growth — by keeping interest rates low — instead of controlling inflation. It has often characterised inflation in a particular month as “transitory”.

In repeated policy statements, Governor Das reiterated that the RBI would do “whatever it takes” to boost growth. But this approach meant that inflation continued to stay high, hurting the poorest the most — and that too at a time when the economic downturn had already robbed millions of poor and even the middle class of their earnings, and even savings.

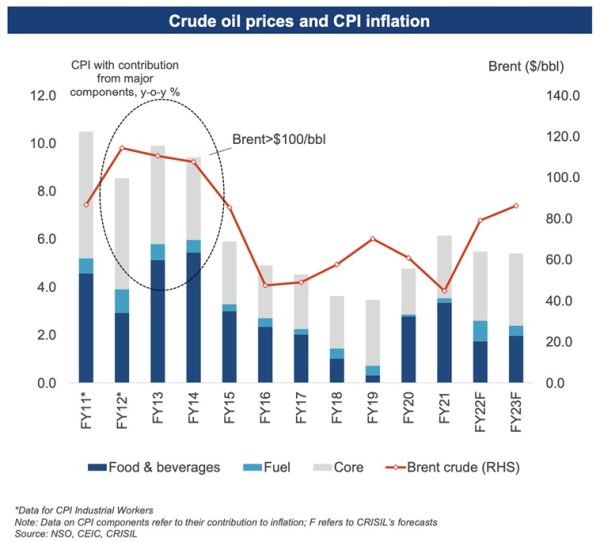

3. The spike in crude oil prices is not new.

In its statement on Wednesday, the RBI has pointed to high crude oil prices in the wake of the Ukraine war, as one of the key reasons for high inflation in India.

But high crude oil prices (See Chart 2 below) were known to the RBI — not just in April, when it met for its last review, but also in February, when it, rather surprisingly, gave the forecast that inflation would be just 4.5% in the coming year.

4. High core inflation is not new either.

The RBI has stated that: “Core inflation is likely to remain elevated in the coming months, reflecting high domestic pump prices and pressures from prices of essential medicines.” Again, evidence shows that over the past year, as the headline retail inflation moderated a bit, the core inflation (which is essentially the inflation rate stripped of the effect of fuel and food prices) had started going up.

In fact, in February, Nomura Research came out with a paper titled, ‘Headline and core inflation converge at ‘six’,’ and it showed how both headline and core inflation were at 6%.

Core inflation going up is often more worrisome because it takes more time to both rise and fall. The prices of food and fuel tend to fluctuate a lot, while core inflation moves up or down slowly.

As such, if core inflation is at 6%, it should have been more worrisome for RBI and perhaps should have prompted policy action.

Newsletter | Click to get the day’s best explainers in your inbox

5. Monetary policy has lags. RBI waited too long.

Often it is thought that as soon as RBI raises or reduces interest rates, the economy will respond immediately. But that does not happen. While such “monetary policy transmission” has improved over the time, yet it can take weeks to have full effect.

In other words, if the RBI wanted to contain inflation in May, it should have acted in February or at least in April. Raising rates right now may not bring down the inflation rate immediately.

[ad_2]

Source link